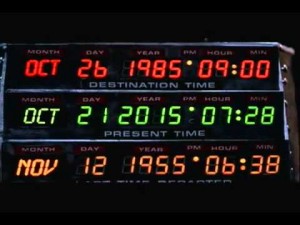

Happy Back to the Future Day! That’s right, Doc Brown, Marty McFly and Jennifer Parker arrive today. Residents of Hill Valley beware!

Happy Back to the Future Day! That’s right, Doc Brown, Marty McFly and Jennifer Parker arrive today. Residents of Hill Valley beware!

And what better day than October 21, 2015 to contemplate the space-time continuum. No, not the mathematical model that joins space and time into a single idea, representing space as three-dimensional and time as the elusive “fourth dimension,” and making time travel theoretically possible. But a more practically useful space-time continuum, for which physicists’ model may serve as a useful metaphor.

I have written frequently about the modern scourge of busy-ness and the secret to having more time. What I always come back to is that there is no way to add time to our days, weeks and months. Not literally. For the time being, human activity is empirically limited by the quantity of time at our disposal.

But there is something about the quality of time—what we choose to do (or not to do) with it—that deeply affects our perception of how much of it we have. In the past, I’ve noted that we can enjoy the experience of “ having more time” by doing and scheduling less—fewer appointments, shorter meetings, less calendar clutter.

By making, or leaving, more space in any area of our lives.

The very word, space, implies a lack of limitation, a certain boundlessness. Space to stretch, move, think, breathe, free from impediment and distraction.

The inherent value of space is taken for granted by nearly every field of study and professional expertise. Graphic design pros and newspaper layout editors dare not fill every square inch with text and images. Rather, they insist on some minimum amount of “white space.” Realtors and home buyers laud open floor plans, while interior designers utilize empty or “negative” space in the placement of a home’s furniture and personal effects. Football coaches tie themselves in knots designing plays that will open up room for their most highly skilled athletes to operate—anything to “get them the ball in space.”

But for all of its obvious technical and aesthetic appeal, space is reliably the first casualty of how we schedule our lives—a sacrifice on the altar productivity and efficiency.

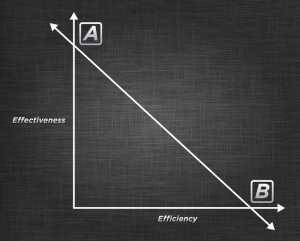

We mistake efficiency for effectiveness at our peril. The cost of operating in tight spaces, both physical and temporal, is the very focus and diligence we aim to bring to our most important tasks.

When we race from bed to shower to Starbucks to school to work (where we scramble from meeting to phone call to “working lunch” to email-triggered fire drill), to Stop and Shop, to rushed family dinner (if we’re lucky), to bath time to story time to Netflix to bed, what are the chances we ever operate at our best? What is the likelihood that we are making the kind of impact we aspire to make?

Great work, strong relationships and restorative rest require that we allot not only time, but space. Empty space in our calendars. Lunch outside the office. A quiet, uncluttered room. Outdoor space. To be alone. To think. To meditate or pray. To write and create. To strategize and plan. Or just, every now and then, to be.

Creating more space means slowing down and prioritizing. It means saying, “no” more than we say “yes.” It means cutting out obligations so that we might enhance our commitment to what is left.

Creating more space means slowing down and prioritizing. It means saying, “no” more than we say “yes.” It means cutting out obligations so that we might enhance our commitment to what is left.

Extreme sports athletes may not be thrashing about on hover boards, Cubs fans may yet have another 107 years to wait, and until Doc Brown arrives, flux capacitor in tow, our best hope for optimizing the time we do have may be to maximize the space in which we allow ourselves experience it.